It Feels Like Irresponsible Groups Are Chanting “Wasshoi, Wasshoi” in Their Anti-Japanese Frenzy

A reconstructed interview chapter examining Asahi Shimbun’s postwar power, covert ties with U.S. operatives, and the media’s role in destabilizing Japanese politics while avoiding full-on revolution. Through anecdotes about war reporting and a notorious “never-disappearing lump” story, the piece argues that today’s anti-Japan narratives stem less from Marxism than from unrestrained hostility and commercial incentives.

May 15, 2019

What follows is a reorganized re-post (paragraphs adjusted) of the chapter titled, “Ryu Shintaro in 1945 Bern as Asahi’s European correspondent with Allen Dulles, the OSS (precursor to the CIA) station chief,” originally published on 2018-05-25.

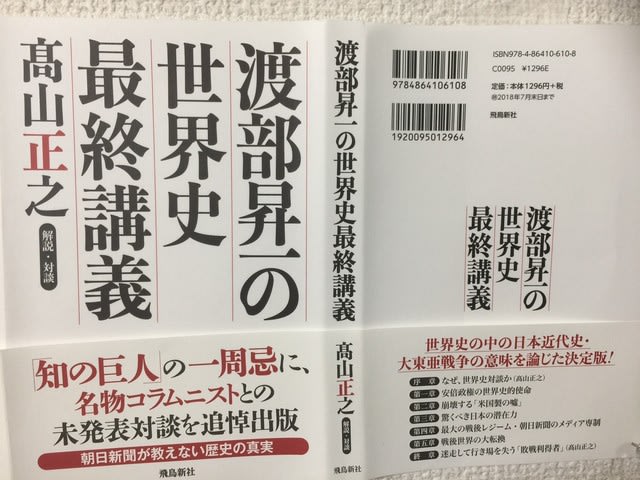

The following is a book strongly recommended to me by a friend who is an avid reader.

For every Japanese citizen capable of reading print, there is no more essential book than this.

Readers should head to their nearest bookstore immediately.

This book alone—see p.146, Chapter 4, “The Greatest Postwar Regime: Asahi Shimbun’s Media Despotism”—will perfectly explain why, over the past year and a half, the print media such as Asahi Shimbun (and those who grew up reading it carefully), the people earning their living in television media, and the opposition Diet members as well as ruling-party politicians like Shinjiro Koizumi have been doing what they have been doing.

Emphasis in the body (apart from headings) is mine.

A Fading Shadow Over Asahi’s Dominance

Watanabe:

I always make sure not to miss anything you write, Mr. Takayama, and it is truly exhilarating.

There has been no one else who has so thoroughly and consistently criticized Asahi as you have.

In recent years, the Asahi Shimbun’s magical authority has waned, and it has become impossible for Japanese intellectuals to gain social standing merely by spreading stories like the Nanjing Massacre or by endlessly attacking Japan with the comfort women issue or any other pretext.

Nowadays, if one wishes to be regarded as a commentator of any standing, one must be seen reading the Sankei Shimbun rather than Asahi.

Takayama:

Thank you very much.

And yet Asahi still publishes article after article that makes one shake their head.

For Japan to recover, the media must be the first to reform.

The United States offers a good example—media outlets there have yet to understand why Trump became president, and they continue their all-out assaults because they refuse to face reality.

The same phenomenon is occurring with their attacks on the Abe administration.

Watanabe:

People are beginning to realize that those who praise the constitution and the occupation policies are fundamentally strange.

It has become clear that there are no truly reasonable voices among the postwar profiteers.

The mass media and cultural figures who profited by attacking Japan have passed their poisonous ideas to the next generation, with Nikkyoso teachers drilling into children that “Japan is to blame for everything.”

The malign influence of these postwar profiteers lingers on.

Those who built their status on anti-Japanese rhetoric cannot retract their positions, even when new historical evidence emerges, because of their pride.

Takayama:

I believe the Asahi Shimbun is the prime example.

At the start of the postwar era, the core of Asahi was its very deep pipeline to the United States.

This was true of Ogata Taketora (former chief editor of Asahi, later director) and also of Ryu Shintaro (former chief editorial writer of Asahi).

Ogata even entered politics, but he was also a CIA collaborator and an agent of Dulles’s operations in Japan.

What America feared most was that Japan might again grow powerful, subdue China, and form a Japan-China alliance that could dominate the world—a scenario Mussolini himself had feared, and what they called the “Yellow Peril.”

To prevent this, East Asia was to be kept perpetually unstable.

Relations between Japan, Korea, and China were to be kept antagonistic, while Japan itself was to remain in disorder.

When Ogata Taketora suddenly died in 1956, Ryu Shintaro, through his acquaintance with Dulles dating back to their time in Switzerland, took over the role.

As a European correspondent in 1945, Ryu Shintaro had been in Bern, Switzerland, where he developed ties with Allen Dulles, then head of the U.S. OSS (forerunner of the CIA), through behind-the-scenes peace negotiations with America.

One piece of evidence of these U.S. ties is the Seven-Company Joint Declaration during the 1960 Anpo crisis.

Asahi even launched Asahi Journal in 1959, whipping up opposition to the security treaty and calling for the overthrow of the Liberal Democratic government.

During a clash between demonstrators and police, University of Tokyo student Kanba Michiko was killed.

With the police reporting some 130,000 demonstrators (330,000 by organizer count), the atmosphere was near revolutionary.

At that critical moment, Ryu Shintaro gathered the Tokyo newspapers and wire services and had them publish a joint editorial declaring, “Reject violence, defend parliamentary democracy.”

Though some attribute the scheme to Dentsu, I am convinced it was Ryu Shintaro’s doing.

Watanabe:

Indeed, it was as though the ladder had been pulled away.

Takayama:

Yes, at the last minute they forbade revolution.

Up to that point, including Asahi Journal, the Asahi’s line had been opposition to the security treaty revision and to the Kishi Cabinet.

They had agitated for the government’s fall, even for occupying the Diet.

But if an actual revolution had broken out, turning Japan into a socialist state, it would have gone beyond America’s design.

So they moved quickly to rein it in.

Among the seven companies Ryu Shintaro gathered was Kyodo News, ensuring the joint editorial was distributed to local papers across the country.

Thus, although the demonstrations raged after Kanba Michiko’s death on June 15, they fell silent after the joint declaration on the 17th.

It was total media despotism.

Watanabe:

Exactly, it wielded overwhelming influence.

Takayama:

And so, how should we assess the Asahi’s stance since then?

Some former Asahi journalists like Hasegawa and Nagae claim the paper was taken over by Marxism, so that its worldview is skewed by the idea “Japan is always in the wrong.”

I disagree.

It is not Marxism per se, but rather a reckless opportunism: “As long as it is anti-Japanese, anything goes.”

Still, during Ryu Shintaro’s time, under U.S. control, there was a final line—media would confuse politics and society, destabilize them, but not permit outright revolution.

When Ryu Shintaro died, however, there was no one left to serve as liaison to America.

Unleashed, the Asahi became like a dog barking anti-Japanese slogans wildly in every direction.

This, I think, explains their tone today; it has little to do with Marxism.

Proof lies in one notorious article.

On September 11, 2010, the evening edition ran a feature “Leyte: The Aging Witnesses,” describing Francisco Díaz, a 95-year-old man living in a thatched hut in Leyte.

The article said, with photo, that Díaz rubbed a lump the size of a clenched fist on the back of his neck, claiming it had remained since 1943 when a Japanese soldier struck him with a rifle butt while he was drawing water at a river.

The lump, they said, had persisted for 70 years.

Watanabe:

A lump like that cannot last 70 years.

I myself recently fell and developed a huge swelling, but it subsided quickly.

There is no such thing as a lump that never goes down.

Takayama:

Indeed. It was nothing but a lipoma, yet they insisted it was a lump caused by the Japanese army, complete with color photos, without any editor stepping in.

What next, are we to believe Kim Il-sung’s supposed lump came from a Japanese soldier’s blow?

It was transparently false.

Simply to portray the Japanese military as brutal, they published this absurd story as if it were a living relic of hidden truth.

Both reporter and editors knew it was a lie, and they did not care.

Their only aim was to vilify Japan.

For them, anything goes if it discredits the Japanese army.

Even the Chūnichi and Tokyo Shimbun, in their 2016 “New Poverty Tales” series, later admitted to fabricating a poor schoolgirl’s story, saying they had “imagined it to make the draft better.”

At least they confessed.

Asahi has neither the self-discipline nor the capacity to admit falsehood.

Watanabe:

If false stories go unchecked, what is the point of editors?

It all looks like a sloppy group shouting “Down with Japan!” while churning out their pages.

Takayama:

It is a bizarre newspaper that exists solely to preach “anti-Japan absolves all.”

They publish stories and photos that everyone can see are fake, without shame.

And readers, persuaded that “the Japanese army was terrible,” swallow it whole.

There is no helping it.

Watanabe:

It is laughable, really—what kind of “research project” would study a lump that never disappears?

Takayama:

A natural monument. A World Heritage Site, indeed. (laughs)